The CUDA Best Practices Guide, a highly recommended followup to this and other CUDA fundamentals labs, recommends a design cycle called APOD: Assess, Parallelize, Optimize, Deploy. In short, APOD prescribes an iterative design process, where developers can apply incremental improvements to their accelerated application’s performance, and ship their code. As developers become more competent CUDA programmers, more advanced optimization techniques can be applied to their accelerated codebases.

The CUDA Best Practices Guide, a highly recommended followup to this and other CUDA fundamentals labs, recommends a design cycle called APOD: Assess, Parallelize, Optimize, Deploy. In short, APOD prescribes an iterative design process, where developers can apply incremental improvements to their accelerated application’s performance, and ship their code. As developers become more competent CUDA programmers, more advanced optimization techniques can be applied to their accelerated codebases.

This lab will support such a style of iterative development. You will be using the Nsight Systems command line tool nsys to qualitatively measure your application’s performance, and to identify opportunities for optimization, after which you will apply incremental improvements before learning new techniques and repeating the cycle. As a point of focus, many of the techniques you will be learning and applying in this lab will deal with the specifics of how CUDA’s Unified Memory works. Understanding Unified Memory behavior is a fundamental skill for CUDA developers, and serves as a prerequisite to many more advanced memory management techniques.

Managing Accelerated Application Memory with CUDA Unified Memory and nsys

Objectives

- Use the Nsight Systems command line tool (nsys) to profile accelerated application performance.

- Leverage an understanding of Streaming Multiprocessors to optimize execution configurations.

- Understand the behavior of Unified Memory with regard to page faulting and data migrations.

- Use asynchronous memory prefetching to reduce page faults and data migrations for increased performance.

- Employ an iterative development cycle to rapidly accelerate and deploy applications.

Iterative Optimizations with the NVIDIA Command Line Profiler

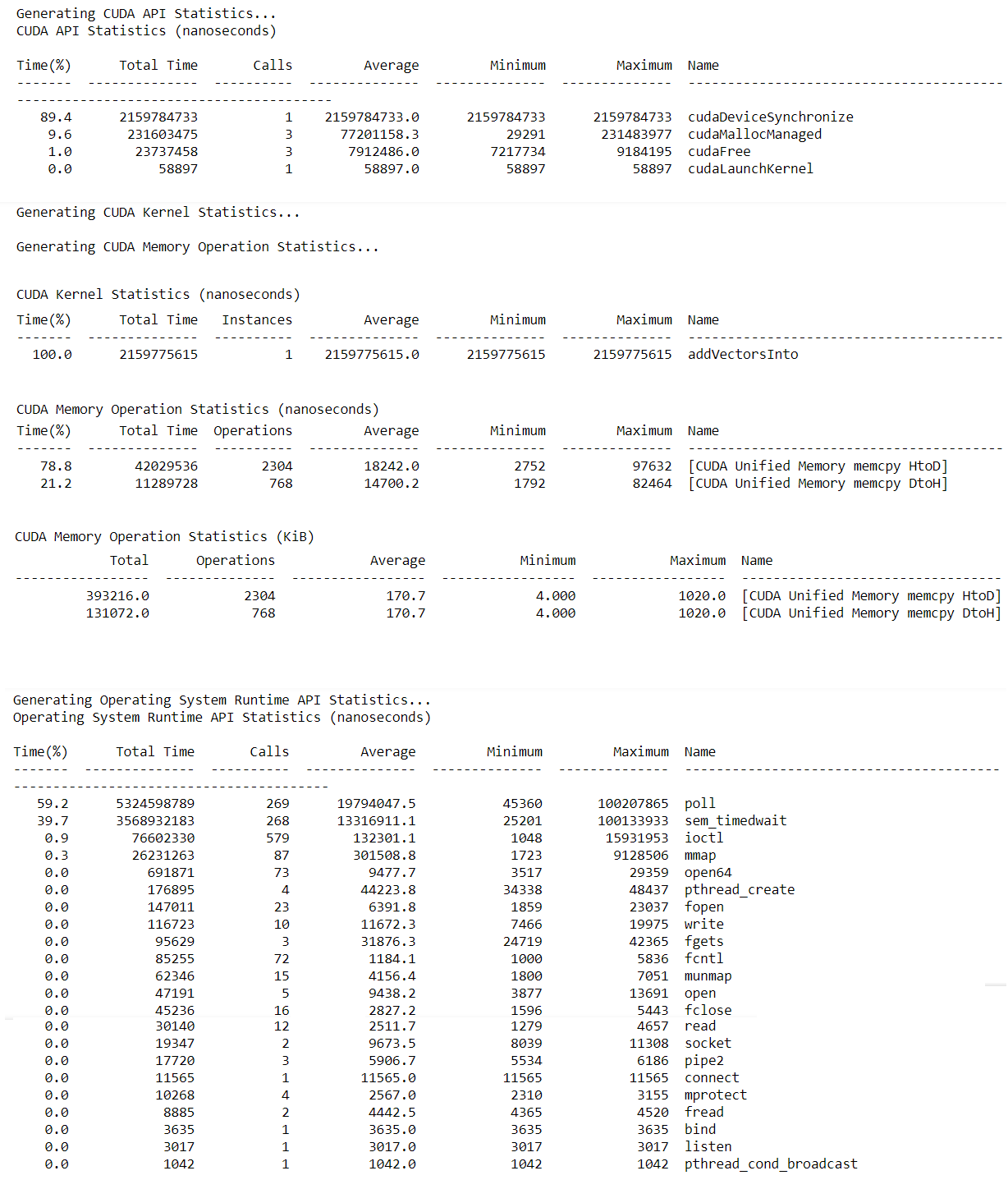

Quantitative information about the application’s performance. nsys is the Nsight Systems command line tool and is a powerful tool for profiling accelerated applications. The most basic usage of nsys is to simply pass it the path to an executable compiled with nvcc. nsys will proceed to execute the application, after which it will print a summary output of the application’s GPU activities, CUDA API calls, as well as information about Unified Memory activity.

Profile an application with nsys

- Code will compile and run the vector addition program.

!nvcc -o single-thread-vector-add 01-vector-add/01-vector-add.cu -run - Profile the executable using

nsys profile!nsys profile --stats=true ./single-thread-vector-add

nsys profile will generate a qdrep report filr which can be used in a variety of manners. Flag --stats=true to indicate the summary statistics printed.

- Profile configuration details;

- Report files generation details;

- CUDA API statistics;

- CUDA Kernel Statistics;

- CUDA Memory Operation Statistics (Time and Size);

- OS runtime API Statistics;

Streaming Multiprocessors and Querying the Device

This section explores how understanding a specific feature of the GPU hardware can promote optimization.

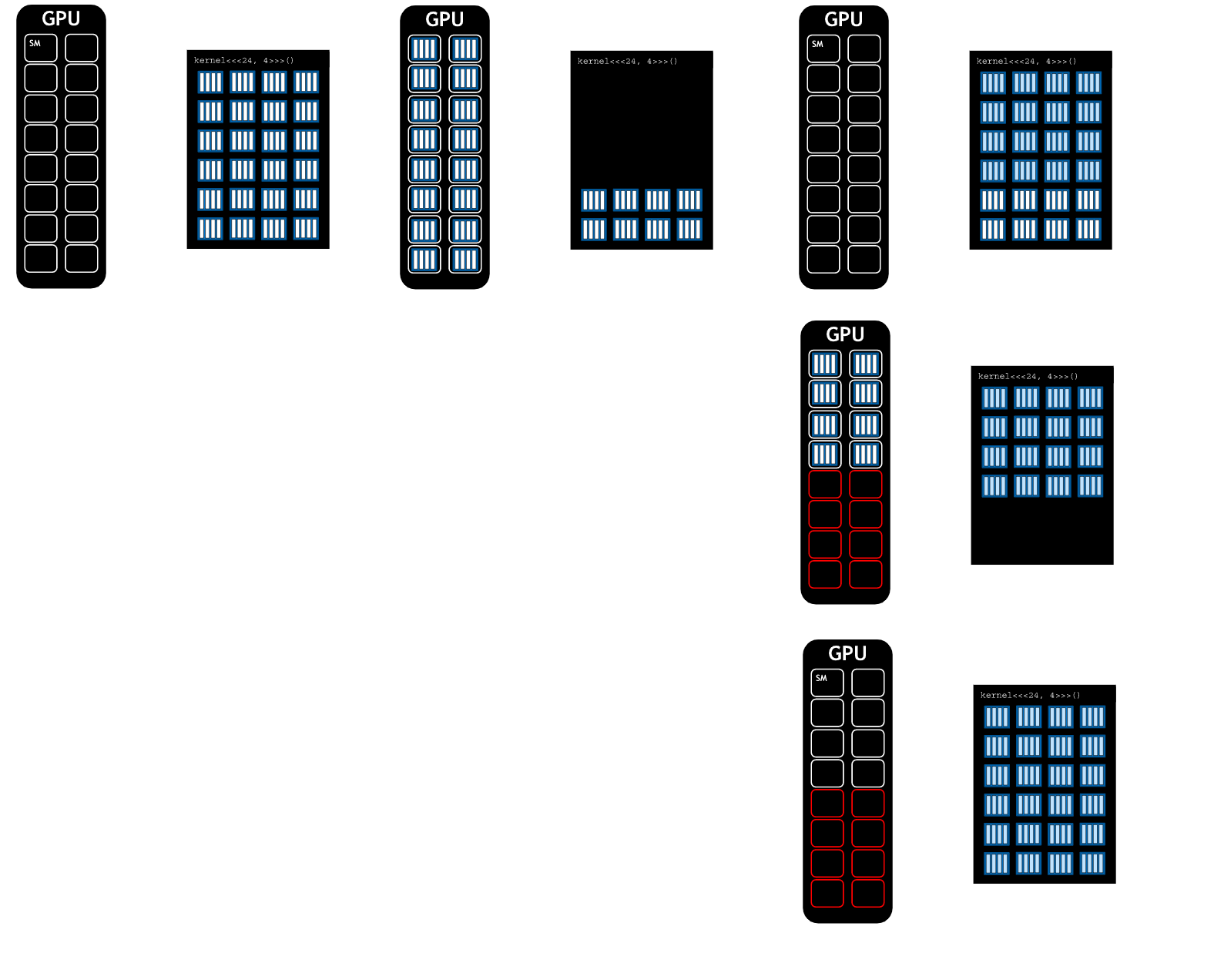

NVIDIA GPUs contain functional units called Streaming Multiprocessors, (or SMs). Blocks of threads are scheduled to run on SMs. Depending on the number of SMs on a GPU, and the requirements fo a block, more than one block can be scheduled on an SM.

Grid dimensions divisible by the number of SMs on a GPU can promote full SM utilization.

Streaming Multiprocessors and Warps

The GPUs that CUDA applications run on have processing units called streaming multiprocessors, or SMs. During kernel execution, blocks of threads are given to SMs to execute. In order to support the GPU’s ability to perform as many parallel operations as possible, performance gains can often be had by choosing a grid size that has a number of blocks that is a multiple of the number of SMs on a given GPU.

Additionally, SMs create, manage, schedule, and execute groupings of 32 threads from within a block called warps. however, it is important to know that performance gains can also be had by choosing a block size that has a number of threads that is a multiple of 32. Coverage of SMs and warps

Programmatically Querying GPU Device Properties

In order to support portability, since the number of SMs on a GPU can differ depending on the specific GPU being used, the number of SMs should not be hard-coded into a codebase. Rather, this information should be acquired programatically.

The following shows how, in CUDA C/C++, to obtain a C struct which contains many properties about the currently active GPU device, including its number of SMs:

1

2

3

4

5

int deviceId;

cudaGetDevice(&deviceId); // `deviceId` now points to the id of the currently active GPU.

cudaDeviceProp props;

cudaGetDeviceProperties(&props, deviceId); // `props` now has many useful properties about the active GPU device.

Unified Memory Details

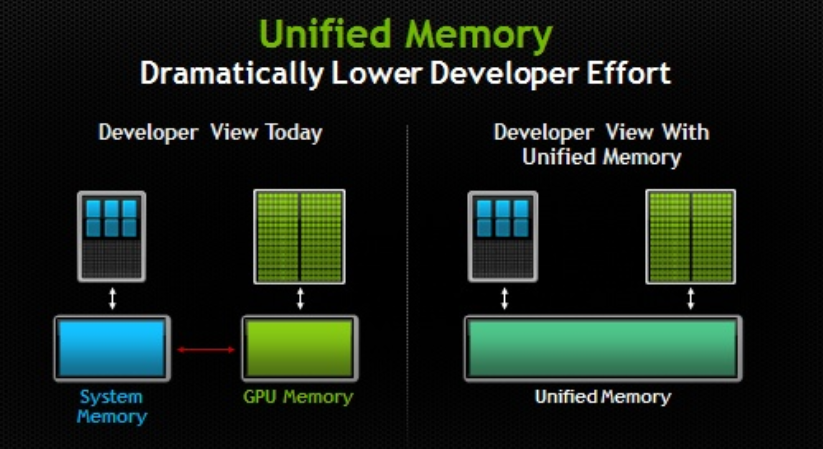

It have been allocting memory intended for use either by host or device code with cudaMallocManaged and up until now have enjoyed the benefits of this method - automatic memory migration, ease of programming - without diving into the details of how the Unified Memory (UM) allocated by cudaMallocManaged actual works.

In CUDA 6.0, NVIDIA introduced UM. In classific PC, CPU & GPU’s memory are physically independent , but connected through PCI-E. Before 6.0, developers shoudl allocate the memory for both CPU & GPU, and manual copy to make sure each end get well-aligned. Unified memory在程序员的视角中,维护了一个统一的内存池,在CPU与GPU中共享。使用了单一指针进行托管内存,由系统来自动地进行内存迁移。

In CUDA 6.0, NVIDIA introduced UM. In classific PC, CPU & GPU’s memory are physically independent , but connected through PCI-E. Before 6.0, developers shoudl allocate the memory for both CPU & GPU, and manual copy to make sure each end get well-aligned. Unified memory在程序员的视角中,维护了一个统一的内存池,在CPU与GPU中共享。使用了单一指针进行托管内存,由系统来自动地进行内存迁移。

for example: (Left is CPU, and Right is CUDA with UM)

for example: (Left is CPU, and Right is CUDA with UM)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

void sortfile(FILE *fp, int N) void sortfile(FILE *fp, int N)

{ {

char *data; char *data;

data = (char*)malloc(N); cudaMallocManaged(data, N);

fread(data, 1, N, fp); fread(data, 1, N, fp);

qsort(data, N, 1, compare); qsort<<<...>>>(data, N, 1, compare);

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

usedata(data); usedata(data);

free(data); free(data);

}

and the difference:

- GPU version;

- using

cudaMallocManagedfor memory allocation, instead ofmalloc; - CPU and GPU are asynchronously,

cudaSyncDeviceeneeds to be called after the launch kernel to synchronize.

before CUDA 6.0, to achieve the above function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

void sortfile(FILE *fp, int N)

{

char *h_data, *d_data;

h_data= (char*)malloc(N);

cudaMalloc(&d_data, N);

fread(h_data, 1, N, fp);

cudaMemcpy(d_data, h_data, N, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

qsort<<<...>>>(data, N, 1, compare);

cudaMemcpy(h_data, h_data, N, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); //不需要手动进行同步,该函数内部会在传输数据前进行同步

usedata(data);

free(data);

}

obviously, the benefits from UM:

- Simplify code writing and memory models;

- Shared a pointer on the CPU and GPU sides without having to allocate space separately. Easy to manage, reducing the amount of code;

- More convenient code migration.

Unified memory migration

When UM is allocated, the memory is not resident yet on either the host or the device. When either the host or device attempts to access the memory, a page fault will occur, at which point the host or device will migrate the needed data in batches. Similarly, at any point when the CPU, or any GPU in the accelerated system, attempts to access memory not yet resident on it, page faults will occur and trigger its migration.

The ability to page fault and migrate memory on demand is tremendously helpful for ease of development in the accelerated applications. Additionally, when working with data that exhibits sparse access patterns, for example when it is impossible to know which data will be required to be worked on until the application actually runs, and for scenarios when data might be accessed by multiple GPU devices in an accelerated system with multiple GPUs, on-demand memory migration is remarkably beneficial.

There are times - for example when data needs are known prior to runtime, and large contiguous blocks of memory are required - when the overhead of page faulting and migrating data on demand incurs an overhead cost that would be better avoided.

Much of the remainder of this lab will be dedicated to understanding on-demand migration, and how to identify it in the profiler’s output. With this knowledge you will be able to reduce the overhead of it in scenarios when it would be beneficial.

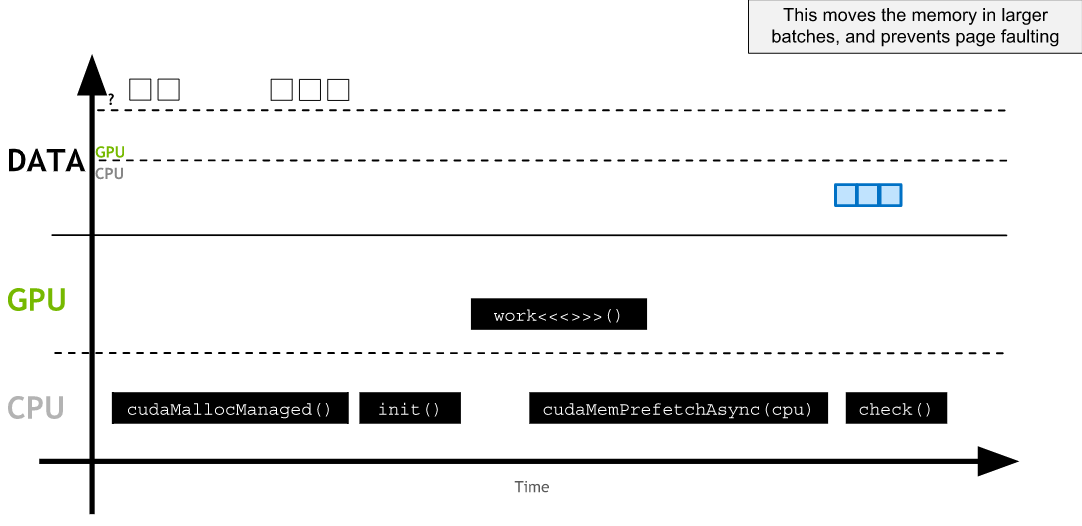

Asynchronous Memory Prefetching

A powerful technique to reduce the overhead of page faulting and on-demand memory migrations, both in host-to-device and device-to-host memory transfers, is called asynchronous memory prefetching. Using this technique allows programmers to asynchronously migrate unified memory (UM) to any CPU or GPU device in the system, in the background, prior to its use by application code. By doing this, GPU kernels and CPU function performance can be increased on account of reduced page fault and on-demand data migration overhead.

Prefetching also tends to migrate data in larger chunks, and therefore fewer trips, than on-demand migration. This makes it an excellent fit when data access needs are known before runtime, and when data access patterns are not sparse.

CUDA Makes asynchronously prefetching managed memory to either a GPU device or the CPU easy with its cudaMemPrefetchAsync function. Here is an example of using it to both prefetch data to the currently active GPU device, and then, to the CPU:

1

2

3

4

5

6

int deviceId;

cudaGetDevice(&deviceId); // The ID of the currently active GPU device.

cudaMemPrefetchAsync(pointerToSomeUMData, size, deviceId); // Prefetch to GPU device.

cudaMemPrefetchAsync(pointerToSomeUMData, size, cudaCpuDeviceId); // Prefetch to host. `cudaCpuDeviceId` is a

// built-in CUDA variable.

Summary

At this point in th e lab, you are able to:

- Use the Nsight Systems command line tool (nsys) to profile accelerated application performance.

- Leverage an understanding of Streaming Multiprocessors to optimize execution configurations.

- Understand the behavior of Unified Memory with regard to page faulting and data migrations.

- Use asynchronous memory prefetching to reduce page faults and data migrations for increased performance.

- Employ an iterative development cycle to rapidly accelerate and deploy applications.

Project: Iteratively Optimize an Accelerated SAXPY Application

A basic accelerated SAXPY application has been provided.

After fixing the bugs and profiling the application, record the runtime of the saxpy kernel and then work iteratively to optimize the application, using nsys profile after each iteration to notice the effects of the code changes on kernel performance and UM behavior.

The end goal is to profile an accurate saxpy kernel, without modifying N, to run in under 100us. Check out the solution if you get stuck, and feel free to compile and profile it if you wish.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

#include <stdio.h>

#define N 2048 * 2048 // Number of elements in each vector

/*

* Optimize this already-accelerated codebase. Work iteratively,

* and use nsys to support your work.

*

* Aim to profile `saxpy` (without modifying `N`) running under

* 20us.

*

* Some bugs have been placed in this codebase for your edification.

*/

__global__ void saxpy(int * a, int * b, int * c)

{

// Determine our unique global thread ID, so we know which element to process

int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int stride = blockDim.x * gridDim.x;

for (int i = tid; i < N; i += stride)

{

c[i] = 2 * a[i] + b[i];

}

}

int main()

{

int *a, *b, *c;

int size = N * sizeof (int); // The total number of bytes per vector

int deviceId;

int numberOfSMs;

cudaGetDevice(&deviceId);

cudaDeviceGetAttribute(&numberOfSMs, cudaDevAttrMultiProcessorCount, deviceId);

cudaMallocManaged(&a, size);

cudaMallocManaged(&b, size);

cudaMallocManaged(&c, size);

// Initialize memory

for( int i = 0; i < N; ++i )

{

a[i] = 2;

b[i] = 1;

c[i] = 0;

}

cudaMemPrefetchAsync(a, size, deviceId);

cudaMemPrefetchAsync(b, size, deviceId);

cudaMemPrefetchAsync(c, size, deviceId);

int threads_per_block = 256; // 128

int number_of_blocks = numberOfSMs * 32; //(N / threads_per_block) + 1;

saxpy <<< number_of_blocks, threads_per_block >>> ( a, b, c );

cudaDeviceSynchronize(); // Wait for the GPU to finish

// Print out the first and last 5 values of c for a quality check

for( int i = 0; i < 5; ++i )

printf("c[%d] = %d, ", i, c[i]);

printf ("\n");

for( int i = N-5; i < N; ++i )

printf("c[%d] = %d, ", i, c[i]);

printf ("\n");

cudaFree( a ); cudaFree( b ); cudaFree( c );

}